Mulling over clothing accessories in downtown Minneapolis, Ellen Dahn figures two retailers offer similar styles at comparable prices. Same for quality and customer service. Then Dahn recalls the uplifting advertisements one store does touting its ties to the Special Olympics; she gets no such emotional tugs from the other retailer. Guess which store Dahn will likely buy from? “With everything else being equal,” says Dahn, “I’d much rather buy from a company I know is doing something for the community.”

For companies that align with social causes or charities, Dahn’s comments are music to the ears. These firms aim to differentiate themselves from the competition by building an emotional, even spiritual, bond with consumers. Standing apart and, in some sense, above, competitors isn’t the only benefit derived by these do-gooder companies. Almost nine in 10 employees feel a strong sense of loyalty to these firms, according to a recent survey by Cone/Roper. And some companies claim they are reaping rising revenues because of their social contributions.

Proponents of cause-related marketing (CRM) say a long, advertised record of community service also offers these enterprises greater customer acceptance of price increases; favorable publicity; and it helps win over skeptical public officials, who often hold the keys to companies’ expansion plans. Those kinds of rewards are a major reason CRM spending has mushroomed more than 300% since 1990.

“As companies find it harder to `out-innovate’ or `out-advertise’ their competitors, deep, substantive, and strategic cause programs that build corporate reputation and brand image will become an extremely valuable leadership strategy in the 21st century,” maintains Carol Cone, CEO of Boston-based Cone Communications, a strategic marketing firm that develops and implements cause programs.

But not everybody’s jumping on the bandwagon. A Cone/Roper survey indicates about half of all companies have programs associated with a social issue. But only a tiny percentage are “cause branders,” companies that Cone says take a long-term, stakeholder-based approach to integrating social issues into business strategy, brand equity, and organizational identity.

Why not? For one thing, companies are still familiarizing themselves with the concept, Cone says. For another, cause branding takes a substantial amount of sophistication, time, effort, and money.

And there are potential pitfalls for firms associating with social causes. Some companies have gotten into heaps of trouble by misleading consumers about their relationship with a nonprofit; others wasted money by hooking up with a charity that offered little synergism. Additionally, quantifying the social contributions is often difficult. Plus, there’s no guarantee that allying with a cause will actually benefit companies.

Image Enhancement

Image Enhancement

Many credit American Express with being the first large U.S. company to install a cause-related promotion to influence consumer purchases. The New York City firm’s 1984 campaign enabled customers to give a few cents from every card usage to restore the Statute of Liberty.

Since then, myriad companies have gotten involved with short- and long-term cause programs. One reason for the heightened interest is that government agencies have been paring funding of nonprofits, prompting many charities to aggressively seek financial and other partnerships with corporations. Meanwhile, some companies have also scored some sizeable benefits by aligning with reputable nonprofits or causes.

These days so many larger corporations are involved that traffic jams are occurring around certain causes. For instance, last year alone it was estimated more than 300 companies hitched their wagon to breast cancer concerns. “The consistency of consumer opinions strongly signals that cause programs are not a passing fad, but rather have become a must-do for brands seeking to strengthen relationships with their customers, employees, communities, and business partners,” says Cone.

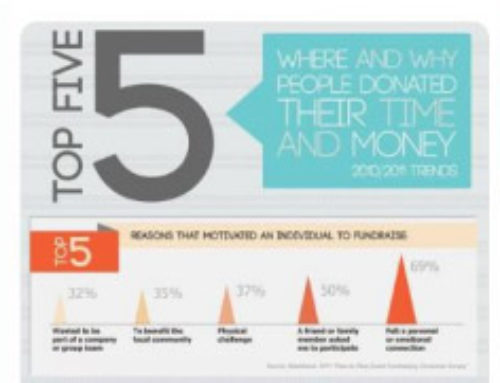

Companies’ participation can take several different forms. It might include outright donations to a nonprofit or cause, which the Cone/Roper survey says is “the most effective and believable activity.” Or, it could involve employees volunteering for the cause or nonprofit, or perhaps donating materials, supplies, public service announcements, and even refreshments for a charity. Wal-Mart contributed more than $100 million in to support children and families through donations, in-kind gifts, and employee volunteerism. The comprehensive community initiatives helped the discount chain bump off McDonald’s as the nation’s leading socially responsible company, at least according to Cone/Roper.

Companies’ participation can take several different forms. It might include outright donations to a nonprofit or cause, which the Cone/Roper survey says is “the most effective and believable activity.” Or, it could involve employees volunteering for the cause or nonprofit, or perhaps donating materials, supplies, public service announcements, and even refreshments for a charity. Wal-Mart contributed more than $100 million in to support children and families through donations, in-kind gifts, and employee volunteerism. The comprehensive community initiatives helped the discount chain bump off McDonald’s as the nation’s leading socially responsible company, at least according to Cone/Roper.

Wal-Mart and other companies’ long-standing relationships with causes are more likely to win consumer plaudits than short-term efforts. The Cone/ Roper survey indicates about eight in 10 Americans prefer companies committed to a specific cause for a long period rather than those opting for multiple causes for shorter times. “The strength of these numbers serves as another indicator that those companies creating deep, relevant, ongoing cause programs will be rewarded,” Cone says.

Forging a longer term relationship also allows a company in some cases to hijack a nonprofit’s reputation and attach enhanced values to the firm’s products and services, according to Marjorie Thompson, co-author of Brand Spirit, a book describing how cause marketing helps build brands. Thompson is director of the Cause Connection at the advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi in London.

Clearly, many corporations partner with cause programs because they believe the bottom line can be enhanced through added revenues and, in some cases, tax deductions. For instance, Visa reported a 17% increase in sales during its “Reading is Fundamental” campaign, compared to sales in the same months a year earlier.

Clearly, many corporations partner with cause programs because they believe the bottom line can be enhanced through added revenues and, in some cases, tax deductions. For instance, Visa reported a 17% increase in sales during its “Reading is Fundamental” campaign, compared to sales in the same months a year earlier.

Similarly, a BMW campaign associated with eradicating breast cancer, in which driving test cars generated a $1 per mile charitable donation, reportedly resulted in sales of hundreds more vehicles. And Wendy’s International in Denver reportedly increased jumbo fry sales by more than a third in 1998 when it contributed a portion of each purchase to Denver’s Mercy Medical Center.

Thompson notes firms allied with social causes are also often granted more leeway in raising product and service prices. She cited a British study that reported almost two thirds of consumers are willing to pay an average 5% more for a product associated with a good cause. “Given the great difficulties which face (corporations) in the constant battle to maintain margins, this should be music to the brand manager’s ears,” says Thompson.

“Nearly two-thirds of consumers report that when price

and quality are equal, they’d be more likely to switch

brands or retailers to one associated with a good cause.”

Adding further credence to the economic value of partnering with cause programs: Nearly two-thirds of consumers report that when price and quality are equal, they’d be more likely to switch brands or retailers to one associated with a good cause, according to Cone/Roper. Some believe socially responsible actions can imbue a firm with “personality” and “niceness.” They also help a company stand apart from the sea of faceless corporations-an important factor for a company, for example introducing a new product, especially considering 25,000 new products were launched last year.

“Since more consumers are buying from firms they believe are making positive contributions to the community, that gives us a competitive differentiation,” says Suzanne Apple, Home Depot’s vice president of community affairs. “Our customers trust us to help them make repairs to their home, and they trust us to be responsible to the community.”

If both the company and customer share similar values, it’s more likely the customer will emotionally and even spiritually bond with the company, says Thompson. And the customer loyalty that should result from that kinship is vital, she says, since it’s far costlier to attract new customers than retain them.

If both the company and customer share similar values, it’s more likely the customer will emotionally and even spiritually bond with the company, says Thompson. And the customer loyalty that should result from that kinship is vital, she says, since it’s far costlier to attract new customers than retain them.

Timberland, a Stratham, N.H.-based producer of high– quality outdoor apparel, footwear, and accessories, enhances its brand-and its bond with customers-by offering them chances to volunteer. “Part of the way Timberland is building a more in-depth relationship with customers is by offering not just an opportunity for a product transaction but for a relationship that takes into account community wealth and value,” says Ken Freitas, Timberland’s vice president of social enterprise.

In some cases, companies use their cause– associated efforts to target new customers. In part, the teaming of BMW, a brand traditionally associated with males, with a breast cancer foundation was designed to grab the attention of a relatively neglected customer base-women, Thompson writes.

Properly executed, cause programs boost a firm’s image, with eight in 10 consumers saying they have a more positive impression of companies that support a cause they care about, according to Cone/Roper. Significantly, 94% of “influential” Americanswhom Cone/Roper calls socially and politically active trendsetters-are more favorably disposed to those companies.

Unexpected Benefits

Atlanta-based Home Depot, has discovered its positive image comes in handy when opening new stores. The home improvement chain’s extensive community activities build good will, a priceless commodity that can counter bad publicity and often aid companies in meetings with public officials. “We believe that if we can tell our story about our commitment to local communities, it makes it easier to get government approvals for a new store site,” says Apple.

Aligning with a good cause can also apparently help recast a company’s image as well.

Aligning with a good cause can also apparently help recast a company’s image as well.

Several companies’ socially responsible efforts have won them considerable notoriety. For instance, Home Depot and Timberland garnered bouquets for winning the Points of Light Foundation’s prestigious corporate community service excellence award. Avon Products, New York, which has raised about $65 million worldwide through its seven-year breast cancer awareness crusade and general support of women’s health issues, has received considerable publicity for its activities, says Patricia Sterling, crusade manager. More than two million women have been educated about breast cancer and more than 500 breast health programs have received funding because of Avon’s efforts, Sterling says. “We had a 60-mile, three-day fund-raising walk in which 2,000-plus people moved down the coast of southern California and camped out in tents,” Sterling says. “It was terrifically mediagenic.”

Another, perhaps unexpected, benefit of cause branding: Corporations learn different operational, management, marketing, recruitment, and retention techniques from nonprofits. The recruitment and retention techniques are especially welcome during these days of exceptionally low unemployment. Perhaps surprisingly, firms’ socially responsible activities apparently have significant effects on employee turnover, loyalty, and esprit de corps.

Nine in 10 employees of firms associated with charitable causes feel proud of their companies’ good works; only 56% of those whose employers aren’t committed to a cause share that pride, according to Cone/Roper. And 87% of employees of firms with cause programs feel a strong sense of loyalty, versus two-thirds of workers in companies without a cause association. “Almost half of the firms who come to us to discuss cause programs do so because of their employees,” says Alison DaSilva, Cone’s director of cause branding and outreach. “When you realize how expensive it is to lose an employee, (those actions) have a significant bottom-line benefit.”

Timberland has discovered its employee volunteer program, largely centered on environmental activities, helps with worker retention. More than 80% of employees take advantage of a generous policy offering them 40 hours annually of paid time off to volunteer. At last year’s 25th company anniversary, Timberland closed down for one day in a “Serv-A-Palooza,” where employees, customers, vendors, and others volunteered in an array of activities.

Avon, which relies on 480,000 U.S. independent sales reps to peddle beauty products, has found its breast cancer education and early-detection program motivates both the employees and the “Avon Ladies,” says Sterling.

Last year, when it was announced at a national convention of 6,000 sales reps how much money had been raised for breast cancer programs, “a roar of cheers rose up from the room giving you goose bumps,” she says. Adds Karen Montemaro, Avon sales rep from Plainview, N.Y.: “I was diagnosed with breast cancer about a year ago, so I appreciate what Avon is doing. I feel more loyalty to the company because it’s helping give me the courage and strength to tackle this illness.”

Last year, when it was announced at a national convention of 6,000 sales reps how much money had been raised for breast cancer programs, “a roar of cheers rose up from the room giving you goose bumps,” she says. Adds Karen Montemaro, Avon sales rep from Plainview, N.Y.: “I was diagnosed with breast cancer about a year ago, so I appreciate what Avon is doing. I feel more loyalty to the company because it’s helping give me the courage and strength to tackle this illness.”

Meanwhile, Home Depot, where break-neck growth requires the retailer to hire an astonishing 2,000 new workers weekly, believes its social cause efforts-involving financial and in-kind contributions and employee volunteerism in four focus areas: affordable housing, at-risk youth, environmentalism, and disaster preparedness and relief-are paying dividends with recruits, says Apple. Once aboard, employees are less likely to leave; the company’s turnover is considerably lower than the industry average, she says. “I’ve had people, both rank and file and director-level, who said our (socially responsible) efforts were a factor in where they went to work,” Apple says.

The Pitfalls

As beneficial as associating with cause programs sound, there are drawbacks. A major pitfall is that, as with many marketing endeavors, it’s often difficult to quantify how well these partnerships work. While Apple cites overwhelming anecdotal evidence of the beneficial effects of Home Depot’s community efforts, she acknowledges that measuring their impact is well nigh impossible: “Measuring a return on investment is very difficult. Many have tried and many have failed.”

It’s also often challenging to attract consumers’ attention to companies’ philanthropic activities. That’s especially true today, when consumers are being constantly bombarded with stimuli from multiple mediums.

There’s also rampant consumer cynicism to overcome, and there’s no guarantee that even a multi-year, multimillion-dollar cause branding effort will do that. Unfortunately, past problems with corporate cause programs stoke consumer concerns. For instance, SmithKline Beecham reportedly paid $2.5 million last year in a settlement with 12 state attorneys general, who accused the company’s consumer health care division of falsely implying the American Cancer Society had endorsed its products. In fact, it was reported, the company paid a rights fee to use the society’s seal, which it then featured in ads for its Nicoderm and Nicorette smoking cessation products.

In part, Avon addresses consumer cynicism by refraining from advertising its role in its breast cancer crusade. Perhaps the best way to address the skepticism is to demonstrate a long-term commitment to a social cause. Home Depot does just that by including “giving back” to communities and society as part of its eight core values. But as high-minded as Home Depot, Avon, and other cause branders are, their commitment doesn’t come cheap. And, unfortunately, being socially responsible doesn’t promise instant benefits.

“The advantages of cause branding don’t happen overnight,” says Cone’s DaSilva, who claims companies should witness benefits three to five years after a program starts. “You have to earn your accolades with action before you can talk about how great (the company) effort is.”

Another obvious but important challenge is finding the right cause or nonprofit to associate with. It wouldn’t be credible, for instance, for a cigarette company to partner with the American Lung Association. Compounding matters, so many companies are doing cause marketing that it’s more difficult to forge a distinctive, attention-getting niche.

Even when a company has sincere intentions and is committed long-term to a cause or nonprofit, problems can arise. “When we started our effort (with breast cancer early detection), we thought it wasn’t controversial,” said Avon’s Sterling. “But it can be just as political and complex as anywhere else, because there are factions within the breast cancer world who think early detection is a waste of time and that every penny should go toward (breast cancer) research.”

Rewarding Stakeholders

No doubt, associating with a cause isn’t for every company. Some firms are hesitant to climb into the social cause arena because of unfamiliarity or possible political repercussions; others, especially smaller firms, may find the commitment, time, and money required too daunting.

And yet for many companies, participating in socially responsible activities appears to help with competitive differentiation, establishing a positive image, employee recruitment and retention, and, in some cases, even added revenues. As Timberland CEO Jeffrey Schwartz notes, community-mindedness also helps a company address all of its stakeholders. “Yes, Timberland is on this earth to make superior boots, shoes, clothing, and accessories,” writes Schwartz. “But that’s not all we do. We create value for our four groups of constituents: consumers, shareholders, business partners, and the community.”

CRM ESSENTIALS

Several key ingredients are needed if companies associating with cause programs are to realize significant benefits:

- Synergy between the cause program and one or more of the company’s strategic business objectives.

- Deep, senior-level commitment, which will help sustain the company’s efforts during its inevitable ups and downs.

- Sufficient resources-resources can take the form of donations, budgeting for advertising, communications or public service announcements, in-kind materials, or employee volunteers.

- A sustained, multi-year commitment to a social cause or nonprofit.

- An open and mutually beneficial relationship with a charity or charities.

- Lots of communication. Discuss what your company’s doing through news releases, newsletters, Internet or intranet postings, and other mediums.

- Measurable results. If a cause program is to be taken seriously as a business strategy, activities must be measured.

- Walking the talk. For example, if your company promotes breast cancer awareness, it makes sense to offer employees breast health education and perhaps pay for mammography screenings.

- Innovation. A cause program maintains freshness by constantly evolving.

Leave A Comment