Cause-related marketing, or cause marketing, has exploded in recent years even though it is a relatively young concept, growing from a $120 million industry in 1990 to more than $2 billion in 2017. Essentially, cause-related marketing is an effort between a business and a nonprofit to raise money for a particular cause.

Both the nonprofit and the for-profit company can enjoy benefits from this arrangement. The company expects to sell more products while gaining public awareness of its values and willingness to support good causes. The nonprofit benefits both financially and through a higher public profile as a result of its partner’s marketing efforts.

How Cause Marketing Began

Cause marketing began on a national scale in the early 1980s, when American Express partnered with a nonprofit group that was raising funds to restore the Statue of Liberty.

American Express gave a portion of every purchase through its credit card to the cause, plus an additional donation for every new application that resulted in a new credit card customer. The company also launched what was at the time a huge advertising campaign.

The results are now legendary: The Restoration Fund raised more than $1.7 million, and American Express card use rose 27 percent. New card applications also increased 45 percent over the prior year. All of this was accomplished with a three-month campaign.

Everyone involved was a winner. The charitable cause received needed funds, and American Express increased sales of its product and achieved a reputation for social responsibility. American Express even coined the term “cause-related marketing.”

Now companies are fully embracing doing well while doing good. Cause-related marketing may eventually become the primary way that businesses express their social responsibility.

How Cause Marketing Works

A cause-related marketing program is not an anonymous or low-key donation to a nonprofit, but one that lets the public know that this corporation is socially responsible and interested in the same causes as its customers. The marketing and PR efforts may come from the corporation’s public relations and marketing departments in partnership with the nonprofit’s marketing.

Cause-related marketing campaigns can appear in a variety of forms. Jocelyne Daw, in her book “Cause Marketing for Nonprofits,” lists some of the most popular:

Product sales. Think of the (Red) campaign, which brought together many companies to sell specially branded products (a red Gap T-shirt or a red iPod, for instance), with a portion of the selling price going to the Global Fund for HIV and AIDS prevention.

Purchase plus. Also called “point-of-purchase,” this popular campaign takes place at the checkout lines of grocery stores or other retail stores. Customers add a donation as low as $1 to their bill, and the store processes the money and gives it to a partner nonprofit. Promotion is low-key, but that makes these programs easy to set up. “Checkout for charity” campaigns raised more than $3.88 billion over the past three decades.

Licensing of the nonprofit’s logo, brand, and assets. Licensing runs the gamut from products that are extensions of the nonprofit’s mission to using its logo on promotional items such as T-shirts, mugs, and credit cards to having the nonprofit provide a certification or commendation of particular products. An example of the latter is the American Heart Association endorsing products that meet its standards for heart health.

Co-branded events and programs. Probably the best-known example of a co-branded event is the Susan G. Komen “Race for the Cure,” but they’re not always runs or walks. For instance, the London Children’s Museum teamed up with the 3M company to build and outfit a science gallery for children. Scientists from the company helped with the exhibits while its employees served as volunteers.

Social or public service marketing programs. Social marketing involves the use of marketing principles and techniques to encourage behavior change in a particular audience. An example is the partnership of the American Cancer Society with several companies over the years for the Great American Smokeout.

Social or public service marketing programs. Social marketing involves the use of marketing principles and techniques to encourage behavior change in a particular audience. An example is the partnership of the American Cancer Society with several companies over the years for the Great American Smokeout.

These cause marketing activities differ from corporate philanthropy, which consists of direct monetary gifts to a nonprofit. Those donations often come from the corporation’s foundation. These donations likely support a particular program that the nonprofit runs and can be of short or long duration.

Corporate sponsorship is a bit closer to cause marketing since the corporation gives the nonprofit money to hold an event, run an art exhibit, or conduct some other time-limited activity. The funds may come from the community relations budget of the corporation or the marketing budget. Usually, the company expects a certain amount of publicity in the way of signage, public service announcements (PSAs), and promotional materials.

Possible Disadvantages of Cause Marketing

There is always the possibility that one of the parties involved in a cause-related marketing program does something to damage its reputation. Because of their association, the other party may be perceived negatively as well. For that reason, corporations and nonprofits should choose their partners wisely.

Some concern also exists over nonprofits lending their good names to for-profit activities. Does it weaken the trustworthiness of a nonprofit? Does it blur the lines between business and philanthropy? Could a nonprofit “sell out” by lending its support to products that are less than benign for the public? These questions continue still hound both fundraising and marketing professionals.

Mara Einstein, a marketing professor, raised these issues in an article in the Chronicle of Philanthropy:

- Does buying products for a cause take the place of writing a check to a charity or going online and signing up for a monthly gift?

- Do large, national nonprofits that have become marketing powerhouses take attention and money away from smaller but just as worthy charities?

- Since cause marketing is usually handled by the marketing department of participating corporations, do “product strategies” outweigh humanitarian ones?

All of these questions are highlighted when cause marketing campaigns go wrong. An example of this is when the Susan G. Komen organization teamed up with Kentucky Fried Chicken to sell pink buckets of chicken to raise awareness for breast cancer. There was general outrage at linking what many consider an unhealthy product to a health-related cause.

On the other hand, great good can come from cause marketing campaigns when all parties choose causes and businesses well.

On the other hand, great good can come from cause marketing campaigns when all parties choose causes and businesses well.

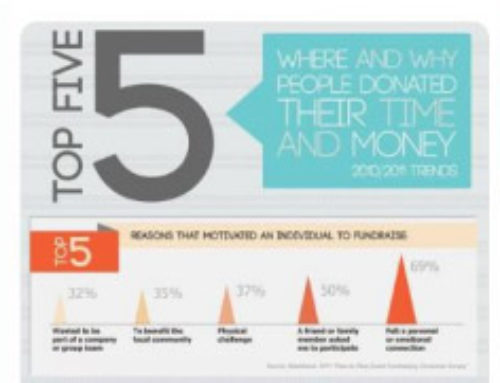

Joe Waters, a guru of cause marketing, points out that there are unlimited possibilities for charities and businesses to do good together. And, as consumers continue to put their money where their hearts are, charities can look for opportunities to take part in the cause marketing world.

Leave A Comment