Printed in The Washington Post (Edited Version)

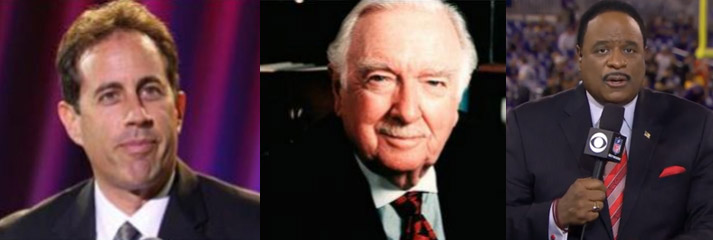

One recent Thursday, Fox TV NFL Sunday co-host James Brown took a swig of water before facing a teleprompter in a Washington, DC TV studio. Sitting on a stool, he deftly recited a script for a public-service announcement on the link between diabetes and foot care that is to begin running on radio and television stations. “What many people don’t know is diabetes is responsible for tens of thousands of lower-limb amputations each year,” he said during several takes, filmed at different angles.

A Personal Connection

For three years, Brown, a popular sportscaster, has recorded radio and television PSAs for the Bethesda-based American Podiatric Medical Association, a national foot doctors’ group. He decided to become the face and voice of the association’s “Diabetes Is a Family Affair” campaign because of his 69-year-old mother’s years-long battle with diabetes. His younger brother and nephew also have the disease. About five years ago, Brown’s mother was forced to have a few toes amputated because of illness complications.

“There was a personal connection with my mom,” Brown, 52, said. “I’m talking from the heart and personal experience.”

Celebrities like Brown have been the spokespeople of choice for nonprofits, industry groups and federal agencies across the Washington region that seek to target listeners and viewers through PSAs.

Unlike commercials, PSA sponsors do not buy media time, instead relying on radio and TV outlets to run the spots for free. But first, organizations must overcome the fierce competition for air time amid the hundreds of PSAs that station directors receive every week. The average television station ran 140 PSAs a week and the average radio station ran 189 PSAs a week according to the District-based National Association of Broadcasters.

Brown’s experience with diabetes and his popularity made him a natural fit for the podiatric association’s campaign, said spokesman George Tzamaras. Thee years ago, the group had sought a celebrity as a national spokesman to boost exposure of its message of the importance of regular foot exams. The PSAs, which cost $40,000 to $50,000 to produce and distribute, were sent to 500 TV stations and 800 radio stations with cover letters requesting that they be aired, Tzamaras said.

“We thought that if we brought in someone like James Brown, we could focus some attention on that part of the disease,” Tzamaras said. “He truly believes in the message; that’s why it works. The fact that he is comfortable enough to share the fact that his mother has diabetes and suffered amputation to part of her foot, it says a lot.”

Celebrities Add Star Power

The National Parks Conservation Association, a istrict-based nonpartisan group that lobbies on behalf of the U.S. national park system, launched a new TV public-service campaign that strategically features its highest number of celebrities — four — in two sets of 30-second ads promoting both national parks and sites in the New York area.

Comedian Jerry Seinfeld, television journalist Walter Cronkite and New York Knicks guard Allan Houston each filmed national and New York spots. Univision talk-show host Cristina Saralegui stars in a PSA that was shot in her Miami studio, said Sandra A. Adams, the association’s senior vice president for external affairs.

The parks group held a fundraiser raising about $ 300,000 from businesses, including PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, International Business Machines Corp. and Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., to fund the campaign and other programs. Seinfeld, Cronkite, Houston and Saralegui were not paid for their participation. The success of the PSAs depends on TV and radio outlets’ generosity in donating air time, Adams said.

“I think the American public and also station managers need some additional incentive to listen to public-service ads,” Adams said. “Having names that people recognize makes an enormous difference. If you’re in your living room and you see a famous face or hear a famous voice, you’re much more likely to pay attention.”

Possible Downsides

But some warn that tying a star to a cause may backfire. Organizations have no control over the direction of a celebrity’s reputation after a spot is filmed, said Jason F. Smith, vice president of Widmeyer Communications, a District-based firm that specializes in PSAs, press conferences and other issue-related communications.

Los Angeles Laker Kobe Bryant, for example, who was charged for sexual assault, appeared as a “literacy champion” for a GTE company reading program. His likeness was featured on posters, inside telephone directories and on calling cards. “You run the risk of partnering up with a celebrity and that celebrity should do or say something afterward, and sometimes your issue has a liability,” Smith said.

The public is also naturally skeptical of the motives of celebrities for participating in PSAs, Smith said. Some viewers, for instance, assume that celebrities are paid or have no real interest in a particular issue. Using stars from competing TV networks is also risky, according to a survey, with forty-one percent of TV stations saying they would not consider a celebrity on a competing TV network, compared with 50 percent of radio stations.

One example of a successful campaign, Smith said, is which features the network’s sitcom stars. One spot featuring Eric McCormack, who plays gay

One example of a successful campaign, Smith said, is which features the network’s sitcom stars. One spot featuring Eric McCormack, who plays gay

lawyer Will Truman on “Will & Grace,” preaches tolerance as McCormack intones, “Hate is a fourletter word. So is love. Which word will you teach your children?”

“If the viewer doesn’t automatically accept that the celebrity would be supportive of the issue, you run the risk of them not buying it,” Smith said. “There’s got to be an instinctive and natural link between the person and the issue, or else it’s not going to ring true.”

If executed well, celebrity-driven PSAs can pay back in dividends, some industry insiders said. Former Chicago Cubs slugger Sammy Sosa filmed a TV PSA in his hometown in the Dominican Republic to promote Habitat for Humanity, said Lena Hendrickson, senior account supervisor at the District office of public relations firm Hill & Knowlton, which managed the production and distribution of the spot.

If executed well, celebrity-driven PSAs can pay back in dividends, some industry insiders said. Former Chicago Cubs slugger Sammy Sosa filmed a TV PSA in his hometown in the Dominican Republic to promote Habitat for Humanity, said Lena Hendrickson, senior account supervisor at the District office of public relations firm Hill & Knowlton, which managed the production and distribution of the spot.

Sosa’s PSA, which ran in English and Spanish and cost $ 300,000 to produce and distribute, was sent to 1,000 TV networks and 2,000 radio stations. Its distribution achieved the advertising equivalent of $ 8.3 million in media value, Hendrickson said.

“He was a cool spokesperson,” Hendrickson said. “He was at the peak of his career and he wanted to give something back to his country. We wanted to reach English and Spanish-speaking audiences.”

The Center for the Advancement of HealthIt rolled out TV and radio spots featuring actor Danny Glover on behalf of its “Saving Our Men” program.. The PSA is designed to encourage African American and Latino men to monitor their health. The spots, which cost about $200,000 to produce and distribute, were funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation of Battle Creek, Mich., said Ira R. Allen, the center’s public affairs vice president.

The Center for the Advancement of HealthIt rolled out TV and radio spots featuring actor Danny Glover on behalf of its “Saving Our Men” program.. The PSA is designed to encourage African American and Latino men to monitor their health. The spots, which cost about $200,000 to produce and distribute, were funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation of Battle Creek, Mich., said Ira R. Allen, the center’s public affairs vice president.

Glover donated his time for the spot, which was filmed in New York, but the foundation paid Glover’s airfare from California, as well as his hotel accommodations, Allen said. Glover was chosen because he is a respected figure among the spots’ target audience of men of color. Having a credible spokesperson helps transfer a message to audiences, he said.

“It’s a personal message delivered by a trusted source in your living room or your bedroom,” Allen said. “That should have a lot more direct impact than a dog-and-pony show.”

Leave A Comment