Cause Related Marketing: Doing Well by Doing Good?

American Express’ Charge Against Hunger Campaign may be a model for cause related marketing, which has been greeted with skepticism and cynicism by some fundraisers since its inception. By putting aside two cents from every purchase made with an American Express card American Express raised $5 million to go to groups fighting hunger in America.

Kmart, Century 21 Galleries Lafayette, and Liz Claiborne raised additional funds in a tiein campaign with the Charge Against Hunger. Stevie Wonder made a personal contribution of $50,000 and Campbell’s Soup Company donated 30,000 cans of food. According to American Express, many members expressed strong support for the entire initiative.

Cause Related Marketing, Risks and Benefits

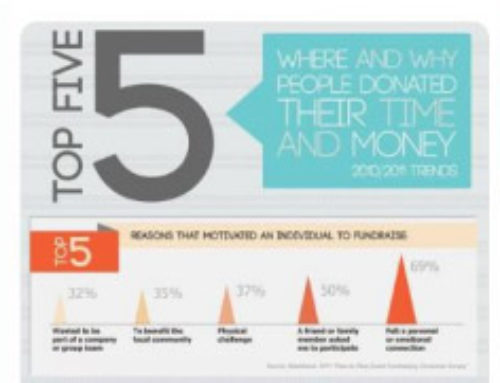

Though this is the largest single amount raised to combat hunger in America, American Express is certainty not acting in a vacuum. According to the Cone/Roper Benchmark Survey on Cause-Related Marketing:

- 78% of respondents said they are more likely to buy a product that is associated with a cause they care about

- 54% percent said they would pay more for it.

- One third of respondents said that after price and quality, a company’s responsible business practices are the most important factor in deciding whether to buy its product.

In a highly competitive market, where products, like credit cards, are difficult to distinguish from one another, a progressive image can provide a powerful marketing edge. Ed Keller, Executive Vice President of Roper Starch Worldwide, which partnered with Cone Communications in the survey, said, “To succeed in cause marketing brands will aspire to people — products will have to meet not only the price and quality demands of consumers, but their personal values as well. Given that environment, cause related marketing is a dramatic way to build brand equity.”

Cause related marketing (CRM) is also a chance for companies to compensate for their decline in traditional corporate philanthropy. According to a recent Conference Board report, corporate contributions have been dropping (after inflation is taken into account), after their heyday in the early 1980s.

Yet nonprofits should pause before casting their lot with corporate America and the consumers of its products. Since CRM is a marketing strategy, corporations will make selections based on perceived attractiveness to customers rather than the needs of charities.

Hunger, which, according to the Congressional Hunger Center, is identified by over 90% of Americans as a problem, is likely to draw far more corporate interest than the more political issues related to empowerment of the poor, gays and lesbians, women, and minorities. The danger, as an Independent Sector survey of CRM indicated, is that “controversial, unappealing, or smaller causes lose out in attracting corporate sponsorships.”

The Cone/Roper survey findings confirm this projection. Respondents indicated that corporations should be doing more to address the problems of crime, the quality of the environment, and homelessness, and that enough has been done in seeking equal rights for minorities and women.

In addition, CRM may end up being just that: marketing. There is the danger that partnerships between companies and nonprofits may be disproportional, where the former uses the image of the latter for its promotions but gives little of substance in return. Bill Shore, founder of Share Our Strength, the hunger relief organization that administered the proceeds raised by American Express, says, “Cause related marketing has the potential to be a very positive thing, if it’s doing something significant rather than giving away a very small amount.”

In addition, CRM may end up being just that: marketing. There is the danger that partnerships between companies and nonprofits may be disproportional, where the former uses the image of the latter for its promotions but gives little of substance in return. Bill Shore, founder of Share Our Strength, the hunger relief organization that administered the proceeds raised by American Express, says, “Cause related marketing has the potential to be a very positive thing, if it’s doing something significant rather than giving away a very small amount.”

Christine Vladimiroff, president and CEO of , Second Harvest Food Bank, offers three criteria in judging a company’s performance in a CRM campaign. First, she suggests, the company should be evaluated for truthfulness in its representation of the cause. Is the issue it is presenting exaggerated? Is the presentation distorted?

Second, the authenticity of statements made and figures used in the press should be verified. Is the company distorting a cause for marketing effect?

Third, the integrity of the process of grantmaking and reporting to the public should be confirmed. Is the company truly donating all or most of the money it raised for a cause to that cause? How closely does the allocation of funds correspond to what was advertised in the campaign?

How open is the company to consumers and to the wider public in disclosing the results of its grantmaking? Is the company showing any long term commitment to the cause it is sponsoring?

Charge Against Hunger

Applying these questions, this article began as an investigative piece to mercilessly uproot any irresponsibility, breach of ethics, or deceit in American Express’ Charge Against Hunger campaign. Yet it could unearth no such evidence. In many ways, the Charge Against Hunger could be a model for other corporations interested in leading a responsible CRM campaign.

The campaign is exemplary in the extent to which it involved employees, the publicity it provided for the problem of hunger in America, the amount of money it raised, the number of agencies it affected, the creative approach it utilized, the degree to which it plans to keep members informed of the results, and the commitment it has shown to sustaining its support.

The campaign was formed in partnership with Share Our Strength (SOS), a hunger relief organization founded by Bill Shore, former campaign adviser to Gary Hart and former chief of staff to Senator Bob Kerrey. American Express’ relationship with SOS goes back several years to its annual sponsorship of SOS’s Taste of the Nation. A week long benefit involving wine tastings and dinners prepared by notable chefs at more than 100 cities across America, Taste of the Nation raises $3 million annually that is distributed to local and national hunger relief programs. American Express employees were instrumental in identifying hunger as an issue the company should address, both through company opinion surveys, and American Express-sponsored volunteer initiatives for its employees.

Speaking to campaign administrators at American Express about the program, one may forget that these are marketing executives. The talk is all of good citizenship and social awareness. Yet choosing hunger may not have been an entirely selfless motive. SOS’s strong connection to restaurateurs may offer an opportunity for American Express to sweeten the bitterness caused when American Express charged a higher service fee to restaurants that accepted the Card back in 1991.

Publicity

Publicity

Nevertheless, American Express is widely praised for the widespread attention it has brought to the issue of hunger in America. “The Charge Against Hunger campaign helped put hunger on the political map,” says Max Finberg, of the Congressional Hunger Center. “It got people to sit up and notice.

No single hunger organization has the access to tap into the mass media the way American Express did.” American Express used its normal advertising budget to promote Charge Against Hunger. Ads ran on primetime TV, as well as during the popular morning show hours. Bill Shore appeared in an interview on Good Morning America, and Stevie Wonder was featured at a Thanksgiving Day Parade and during the Superbowl singing a song he wrote for the campaign.

Truth in Advertising

Truth in Advertising

Other kudos went to American Express for doing what it said it would. One press conference was held at the start of the campaign to announce the company’s intention to raise and donate $5 million for hunger relief, and another to declare that the goal had been met. True to its promise, the $5 million was distributed widely, to a total of 257 recipients in all 50 states. In addition, American Express donated $200,000 to SOS in administrative grants so that all of the $5 million raised could go directly to hunger relief.

A creative and thoughtful approach characterized the campaign, one which sought to make hunger relief organizations and those who depend on them self-sufficient. Five allocation categories were established, including expansion of federal school breakfast programs, perishable food rescue projects, food assistance programs in underserved areas, Super Pantry programs to teach nutrition and food preparation to people who regularly use food banks, and child malnutrition clinics. The programs targeted “America’s fastest growing segment of hungry people, children and their families,” according to an SOS brochure.

Integrity

The integrity of the allocation process was another area where the campaign can be commended. In any large scale CRM campaign, there is the chance that only a few favored cronies may receive the proceeds, or that the availability of funds is not widely communicated to interested groups.

In this campaign, Request for Proposal forms were distributed through all the major hunger relief networks. SOS estimates that 80% of recipients had never received money from SOS before. The average grant size was $20,000, although some grants for school equipment were as low as $1000 and one grant for the national Campaign to End Childhood Hunger was $305,000.

The impact that grants will make varies. The Kentucky Food Bank, for example, with an annual budget of $370,000 received a $2,000 grant that will allow it to extend credit to four needy agencies that depend on the Food Bank for supplies. The Farm Project of the Capital Area Community Food Bank in Washington, D.C., however, with a budget of $53,000 last year, received a grant of $20,000. The Farm Project, which grows produce for low-income people, will be able to increase its crop from 11,000 pounds of produce last year to 25,000 pounds this year, and 30,000 pounds next year.

Approval criteria included the following: clearly defined and realistic goals; meeting local needs and capacities; having the potential to make a significant impact; demonstrated stable and effective operations; and a demonstrated financial need.

“SOS has an extensive nationwide network and has done a good job in getting the money out,” commented Christine Vladimiroff of Second Harvest.

Recipients are expected to spend the money in the way outlined in their proposals, and are asked to submit a six-month and one-year assessment of what impact the money had. In its expectations of grant recipients, “SOS strikes the right balance between accountability and flexibility,” says Ms. Finberg of the Congressional Hunger Center.

Commitment

The Charge Against Hunger grows out of the commitment to hunger issues that American Express displayed in its support of Taste of the Nation. It plans to extend this commitment by running the campaign again next year, with the hope of raising another $5 million. “There’s an equity in doing it a second time,” said Gregory Tarmin, public affairs manager for the campaign at American Express. “People know more about the issue and have an added chance to get involved.”

Accountability

A key concern about CRM is how to insure philanthropic accountability in the context of corporate marketing needs. No law requires a corporate sponsor to disclose whether and how it spends funds raised in a CRM campaign. The absence of regulation opens the field to abuse of the public trust.

In this respect too, officials at American Express appear concerned about maintaining accountability to their members. SOS has recently completed a list of grant recipients, which included names, grant amounts, and intended purposes.

Natalia Cherney, who managed publicity for The Charge Against Hunger Campaign at American Express, says a key focus of the next few months is communicating to cardmembers and service establishments through newsletters, brochures, press releases, and advertisements where their money went and how it was spent.

Although finding a corporate sponsor may not be easy (SOS has not been approached by other corporate sponsors), the Cone/Roper survey suggests that cause related marketing will be a growing trend. Any non-profits who do partner with a company in such a campaign must be prepared to ask the right questions. Otherwise, they may just end up buying a lemon.

Leave A Comment